“It’s only a paper moon, sailing over a cardboard sea.

But it wouldn’t be make-believe, if you believed in me.”

(“Paper Moon,” Harold Arlen, Yip Yarburg, Billy Rose)

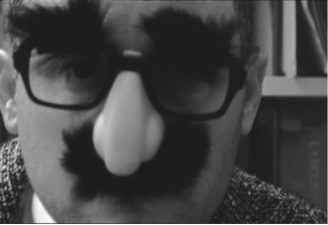

Many have asked me: Why do you wear a Groucho nose and glasses?

The results of a Google search for “groucho glasses,” suggests that they are ubiquitous as party and costume store props. The Wikipedia entry proposes that they are “shorthand for slapstick.” Whether there is a direct association to the legendary comedian or not, putting on the glasses signals the intent to be funny in a pointedly off-beat, yet strategic way. The first time I used the disguise was for a slide talk at an academic conference. Presenting an image of myself as a mad professor was meant to send up scholarly assertions of authority by undercutting the certainty of my own arguments. This was a self-serving gesture- -a way to express my own critical sophistication–but it was also meant to put the audience on notice to check their own assumptions. The Groucho disguise is a type of mask, but one that incorporates something of what you already look like, so the wearer does not so much hide behind Groucho’s face as adapt to it. The face is you and it is not you, you are serious and you are kidding, contradictions that open a path to eccentricity and irony. For most of his career, Marx applied stage make-up to create his bushy moustache and eyebrows and so even Groucho Marx had to become the character of Groucho Marx.

On the social networking site Facebook, the face is the coin of the realm, as each “profile picture” represents a form of identification, a statement of intent, and a direct link into the details of the participant’s life. I registered with the site about two years ago, but was ambivalent almost immediately. Checking out the scrolling “news feed” with it’s short, frequent commentaries and announcements of professional and personal events–art exhibits, political expressions, vacation plans, celebrity gossip, family milestones from birthdays to toilet-training–rarely draws me in. When invited to respond, I usually do, but even then the exchanges are not satisfying and intimate in the way e-mail can be. In contrast, entering Facebook feels like standing on a line that has no visible beginning or end. Wherever it is going, it is moving quickly and has it’s own agenda, so you have to talk fast and frequently to get anyone’s attention. That may be the point and pleasure of it, to jump on and off the train whenever you choose, but everyone on Facebook has needs and sometimes I don’t want to compete.

I chose my Groucho photo in order to enact some resistance to the mostly cheerful give and take that characterizes the circumstances of my affinity group. Social utility may be in the eye of the beholder, but neither I nor any of my Facebook friends was posting from Tahir Square in Cairo a few months back. Like many others on Facebook, I chose not to show a photo of the real (public) me, in order to better express the real (private) me. This is of course a weak retort since the whole mechanism of the site is defined by alternating veils of disclosure: here are my likes and dislikes, desires and accomplishments, exposed to a collective of personal friends and affiliated “friends” invited into my Facebook list. More importantly, my character was meant to suggest that I was curious, and thinking about the other adjacent faces vying for time and real estate on the screen. On Facebook, signs of validation are implicitly and institutionally encouraged–thumbs up, thumbs down–if not the heart of the matter. Even as ideas and appeals, trivial or powerful, flow and connect through the varied social networks, the individual post is the bid for attention that plants the seed.

So, in lieu of sending informal messages, I began to periodically upload short videos where I sang songs that referred to friends or faces. There was one where joined by a crew of rubber toys, I sang a duet of “That’s What Friends Are For” with Dionne Warwick. In another I sang my version of “For All the Girls I’ve Loved Before” with Willie Nelson and Julio Iglesias: “For those who were untrue, I’d have to say fuck you, to all the friends I’ve loved before.” I had the hope that some on the Facebook page would get the joke, or at least acknowledge the fragile and schematic facts of our virtual community ties–one face and one ego to another. Unfortunately the response to these videos was minimal at best considering the vast numbers of potential viewers on hand. I only received comments from people who I already corresponded with by other means.

This was disheartening, and I also felt offended that my videos, which were produced with some forethought and production time, had no more weight or pride of place in the news feed than the most casual comments or ad hoc photos. Oh yeah, “posted an hour ago.”

On Facebook and in the more elaborated singing videos on my www.greatblankness.com website, the Groucho nose and glasses play a pragmatic role in providing some distance between my actual face and what I see when I look into the mirror of the MacBook screen camera and talk or sing. Feeling less self-conscious about the qualities of my voice, facial expressions, and mannerisms allows me to retain a reserved, yet flexible stance, which can shade into resignation, bemusement, or doubt depending on the narrative.

Often my Groucho disguise is abetted by a felt fedora. While the fedora apparently started out as woman’s hat worn by Sarah Bernhardt in the late 19th century play Fédora, for men it has played a role in film-noir gangster movies; been paired with sunglasses and associated with hipness as with the Blues Brothers or jazz musicians like Thelonious Monk, adventure heroes like Indiana Jones, and visual and performance artists like Joseph Beuys. Why the fedora could serve all these masters has I think something to do with the association to adult, bourgeois concerns, so when worn by people doing unconventional things, it becomes a way to both flout and inhabit conventional style: As art and music are meant to incorporate sustained work, and provocative play, culture has business to attend to. Serious clowns earn the right to wear fedoras.

Sometimes I wear other hats, as with the folded newspaper version above. While this refers specifically to my rendition of “Paper Moon,” it is also a way to link comedy to the sentiments of the songs without wholly undermining them. Here the juxtaposition of Groucho disguise, paper hat, and sober black turtleneck is a sight gag that creates some friction with the lyric’s desire that love will embody something more lasting than fantasy–“It wouldn’t be make-believe if you believed in me.”–which in turn collides with the belief, strongly endorsed in grade school, that creativity will lead to happiness. In this way, pop standards can function as a kind of audio clip art suitable for various occasions: the sometimes stereotypical themes explored–true love, unrequited love, lost love–are no less evocative for their reliance on melodrama and fantasy. In musical terms, these songs have effective hooks. Still listening to the sound of one’s voice (on screen or in the shower), may be enough of a reward.

The singing videos on greatblankness comprise a cycle called “Songs of Love and Rage.” The last video in the series revolves around the Brandt/Haymes standard “That’s All,” and for most of it, I share the screen with a Mr. Potato Head toy. Late in the video, I remove Mr. Potato Head’s eyes, nose, and mouth before taking off my own disguise to sing the last verse. While Mr. Potato Head loses his assembled face, I become “myself” for a time. Parenthetically, however viewers may respond to this, I feel I look older than I like to think I do, so that when the last verse is done, and I put the Groucho disguise back on I think it improves my appearance. Either way, this is a choice I have denied to Mr. Potato Head who, plastic and ageless, is left in a sympathetic state of confusion and wonder, neither clearly in love nor enraged. We humans are fortunate to have control over so many options.

The last verse of “That’s All” goes: “If you’re wondering what I‘m asking in return dear, you’ll be glad to know that my demands are small. Say it’s me that you’ll adore for now and evermore, that’s all, that’s all.” In other words, I need the audience to embrace me with or without my disguise. OK?

An unusual variation on this psychic feedback loop (which surprisingly also involves singing) is a recent Facebook message sent by a summer camp friend who I had not seen since 1960. Attaching a black and white photo from that time, he asked whether the person in the Groucho disguise was the same as the one in the camp photo: “Is this you behind the disguise?” It was–I’m the shorter kid in the t-shirt–and this led to a series of warm exchanges about the past and the present. Seemingly random, out-of-the-blue, connections is another benefit that Facebook may provide which one may choose to embrace or avoid.

In the end, I should acknowledge that the “many people” who have questioned my use of the Groucho disguise are actually just a few thoughtful friends who wondered why I would choose to place a disguise between my real face and the audience. One pointedly saw the potential for an anti-Semitic stereotype in the large nose and glasses, a speculation fraught with fears about necessary vigilance and unnecessary suspicion. Although the Marx Brothers were jews who as far as I know had the noses they were born with, both jews and anti-semites may sometimes feel the need for disguise. With others, there was the suggestion that I was using Groucho to deflect, if not hide from, the sincere implications of the songs. I would argue that this was also a way to give the audience some space to identify with the songs without having to identify with me. Most likely it is both. From Walt Whitman’s “One’s Self I Sing:”

“Of physiology from top to toe I sing:

Not physiognomy alone, nor brain alone, is worthy for the muse…”

(PZ, June 2011)