In the summer of 2004, I traveled to Brazil with my wife and a colleague from LA County Museum. Initial stops in Rio de Janiero and Sao Paulo were taken up with visiting art galleries and museums, and multiple colonial era churches– research for our friend. This was followed by a trip to the scenically breathtaking city of Ouro Preto in the mining region in central Brazil, and then up to the capital city of Salvador in the northeast state of Bahia, the heart of Afro-Caribbean Brazil. One afternoon in Salvador, we drove to the old town center of Pelourinho which was filled with funky tourist oriented shops, centered around the Igreja do Bonfim church. Numerous street peddlers were aggressively selling ribbon bracelets called “fitas,” descendents of 19c silk versions which bore Catholic symbols of devotion and thanks (ex-votos).

The primary marketing technique involved the peddlers forcibly tying the bracelets to your wrist for a test run of sorts, in anticipation of a donation of an unspecified amount. In the absence of any overriding belief in religion or magic, or fascination with the anthropology of consumerism and faith, all that remained for me was the guilt that a tourist might feel to provide income to a poor peddler. I have had that response before and acted on it, but not this time.

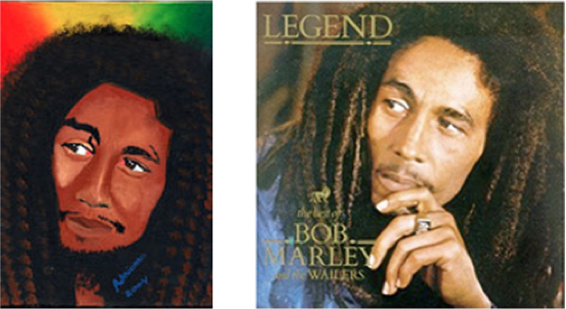

Walking away from the church, we passed a group of shops displaying local paintings, primarily folkloric landscapes and seascapes. In one of the shops I noticed a small portrait of Bob Marley that was unique among the repetitive scenes of local color and pastoral life. No more than 8 x 10 inches, it was a head shot of Marley with long dreadlocks and soft-focus vertical bands of red, yellow, green–the colors of the Jamaican flag–behind his head. I assumed it was copied from an album cover or poster, but it was carefully painted and simply composed with Marley looking thoughtfully to the right.

We returned to the town center the next day, largely to revisit the painting and perhaps inquire about buying it. The man at the shop was glad to take it off its hook and show it to me and when I asked the price and it came to about $14 US. Assuming that a tourist is supposed to bargain in a developing country, I used gestures and broken Portuguese to express my disappointment. Too expensive! This did not seem to impress the storeowner and in fact he seemed offended, but I assumed that this was part of the game. I once again questioned the price and then started to walk away expecting him to run after me, but he didn’t.

I met my wife and friend around the corner, described what happened, and both thought I was an idiot for not spending $14 on something I so clearly admired. Sheepishly, I walked back to the shop, and gestured yes to the owner who now seemed thrilled. I learned that he was in fact the artist (named Adriamo) who made it. That it was rendered in oil not acrylic made it considerably more valuable in his eyes. After spending a few minutes showing me photos of his other works collected in a folder, Adriamo wrapped the painting in glassine and newspaper and I happily took it away. It has hung in a prominent place on the wall above my computer ever since.

When I look at the picture now I see the artist’s commitment to his trade: a synthesis of aesthetic choices, technical skills, and careful observation. Whether this painting meets some notion of a professional standard seems irrelevant, but what gives it amateur status? A painting hanging in a shop for tourists is made for casual sale, not critical validation, yet is no less calculating in its desire for attention than one in a museum. For me, the Marley portrait, became a gift tied to a particular time and place. Was it good fortune that led me to it? Both as a painting and as a souvenir of the trip to Brazil, it gives me pleasure every day.

POSTSCRIPT

In the years that I have had the painting, I never looked for the source of its image, until now. A quick search on the Amazon.com website for Marley’s albums brought up an image of the “LEGEND” LP which is clearly the model for the picture. The artist has left out the text, Marley’s hand, his blue shirt, and added the Jamaican corona of color. While this does not radically change the image, it does undermine my sense of Adriamo’s skills as I now have to wonder whether his decisions were less pure than I chose to believe. Maybe he couldn’t paint a hand, but worse I now see an absence (filled with his signature) where the hand should be.

In the album cover photo, Marley’s hand on his chin reads as both self-protective and thoughtful; just like a wary but enlightened tourist. In the painting, Marley’s face is literally more exposed, but with his thick cable-like dreads, and more sculpted features, also more intensely iconic. Like a tribal mask. Photo or painting: denatured celebrity portrait versus passionate, awkward interpretation. Artistic license is a given, but in all cases, innocence dies hard.

–PZ, January 2011